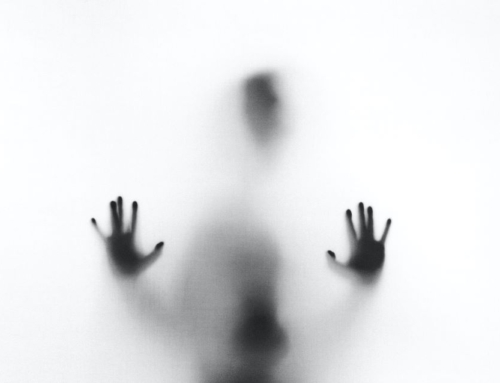

Avoidance: How Seeking Safety Can Turn Into Self-Destruction

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

Everyone has times when they avoid things they don’t want to deal with. Whether it’s a painful feeling, a difficult conversation, a dreaded phone call … avoidance is part of life.

It’s natural to want to shield yourself from the anticipated discomfort of many situations. But when avoidance becomes chronic and interferes with the activities of daily living, it can wind up increasing the very discomfort you are hoping to avoid. The temporary relief gleaned from avoiding something does not make the situation go away and is actually more likely to make revisiting the inevitable that much worse.

Avoidance is a broad topic of research in the field of psychology. It’s generally tied to anxiety and viewed as an effort to protect a person from distress. It manifests in a wide spectrum of problems, from common issues with procrastination to something more extreme like agoraphobia.

Psychological Avoidance

As a survival response, avoiding danger can be lifesaving. In fact, all animals learn throughout their lives how to predict and avoid things that might hurt them.

However, when it becomes a habit or when threats are perceived everywhere, avoidance can wind up having the opposite effect, ultimately exacerbating the discomfort.

Like everything, avoidance exists on a continuum of severity. It can be understood better by looking at some of the patterns and types of behavior associated with it.

Author and professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School Luana Marques, PhD defines different avoidance patterns in an article written for the Washington Post, entitled “Avoidance, Not Anxiety, May be Sabotaging Your Life”. Below are some of the avoidant behaviors he describes as both common and destructive:

Retreating is what one usually thinks of when discussion avoidance. This is when you distance yourself from an uncomfortable person, issue, or situation. This can manifest in a lot of different behaviors, like dodging the source of anxiety altogether, using substances to numb or ease the discomfort, or occupying your attention with screens or other means of distraction.

Experiential avoidance is also a commonly understood form of avoiding. This is when you are unwilling to experience or sustain a connection to internal thoughts, feelings, sensations, or memories that are uncomfortable. Instead, you will develop ways to escape the experience. Substance abuse, self-harming, and dissociative behaviors are all examples of experiential avoidance. Daydreaming, wishful thinking, and fantasy can also be considered forms of avoiding something experiential.

Remaining is when you avoid things that fall outside of the zone of what’s familiar. This is often due to fear of the unknown or change. For instance, this type of avoidance might lead you to choose to stay in a relationship that feels unhealthy or even abusive because there is comfort in knowing what to expect.

Reacting may seem like the opposite of avoidance due to the fact that you are directly engaging with the source that feels dangerous. Yet, it is a form of avoiding because instead of addressing the discomfort or conflict directly, you may overreact with heightened emotions that lead to behaviors like yelling or confronting. The intention, whether conscious or not, is to eliminate the initial trigger rather than truly engage with it.

The Role of Trauma in Avoidance

Avoidance as a behavior becomes more intricate when considering individuals who have a history of complex trauma. Here, experiential avoidance can be viewed as a survival response that becomes activated when the body’s biological stress system perceives danger, even when it’s not there. This is because the body’s natural stress response system has been activated with so much regularity that it becomes habitual and continues to flood the body with cortisol – a stress hormone that signals the nervous system to act quickly and manifests in fight, flight or freeze behavior. For some people, this can lead to chronic disconnection and dissociation, making it difficult to perform certain activities and engage in relationships.

Although it may be a form of protection, avoidance of conflict, trauma reminders, vulnerability, intimacy, etc., can over time lead to heightened trauma responses, anxiety, depression, and loneliness.

Risks and Consequences of Avoidance

There are some risks that emerge from leaning on avoidance as a means of escaping difficult or challenging feelings or experiences. Although avoidance might provide you with a temporary sense of relief, if it becomes chronic you may never really learn how to navigate those challenges. This can develop into a self-perpetuating cycle of avoidance to cope, ultimately limiting possibilities for growth and connection.

Research has linked avoidance with an increased likelihood of future depression.

When anxiety leads to limiting your exposure to uncomfortable situations, then you’re also less likely to experience any potential positive effects of exposure to the perceived threat.

For instance, if you avoid social situations due to fears of rejection then you miss out on the opportunity of finding connection despite your anxiety. Or in the case of agoraphobia, you’re less likely to experience the physical and psychological benefits of exposure to nature – a major healing factor in emotional distress.

With limited positive experiences, your outlook can become biased towards feelings of hopelessness and eventual depression or even suicidality.

Avoidant Behavior Can Change

If you find yourself using avoidance to a degree where it is interfering with your productivity or feelings of wellbeing and connection with others, here are some ideas to consider:

- Where and when do you find that your fears are dictating your choices? Consider what you are afraid of and try taking small steps to address the fear. For example: If you are afraid of speaking in front of people, you can practice in front of a small group of trusted friends. This gradual exposure to your fear can allow you to be less panicked when you have to speak in a larger group of colleagues or strangers.

- Check in with your thoughts in response to situations you find yourself avoiding. Chances are you may be using black and white thinking, which can make things feel bigger than they are and/or impossible to overcome. For example, saying to yourself, “I could never …” is an automatic way you might be talking yourself out of opportunities without even trying to imagine their potential. These are distortions in your thinking that may need to be challenged

- Practicing mindfulness can assist in challenging avoidant behavior and help you to lean into your difficult emotions. Through mindfulness, you learn how to expand your tolerance for discomfort. With consistent practice, this can shift you away from automatic, negative thinking and open up possibilities for more positive experiences.

At the end of the day, avoiding what feels scary, overwhelming, and/or exposing makes sense. You want to protect yourself. In fact, avoidance may have helped you survive traumatic experiences in the past. However, in the long run avoidance stops being a tool for survival and starts to become a barrier to living. Sometimes, facing your fears is truly the step towards healing and recovery.