Why Ending Therapy Should be a Goal

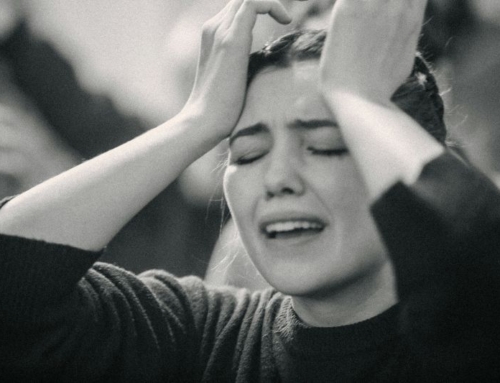

Photo by Junseong Lee on Unsplash

I recently read an article in The Atlantic titled “Plenty of People Could Quit Therapy Right Now” by the psychiatrist Richard A. Friedman. He makes the very solid, if not seemingly controversial, argument that therapy should not be a forever thing. Except in the most extreme and rare of circumstances, he argues, the goals of therapy are for you to be able to live your life without depending on therapy. He further states that for many, ending therapy just might be what they need to actually move forward in their life.

This may seem like a strange thing for a mental health professional to propose, seeing as we obviously rely upon clients to pay the bills. In fact, that is likely one of the reasons that many clinicians will allow clients to essentially stick around forever. But the thing is, as a professional it is my (and my colleagues’) duty to stay focused on what we are trained to do rather than what makes our lives easier. What we are trained to do, of course, is therapy.

Defining Therapy

There are many different kinds, brands, and flavors of therapy on the market. Some are short-term, focused on acute symptoms like panic or mild anxiety, while others are longer-term, focused on more long-lasting and deeper change. Therapies that are truly trauma-focused, especially when considering complex trauma, are almost always long-term.

Regardless of the brand of therapy, they all share one thing in common: To help clients reach a certain set of goals in order to improve functioning and decrease distress.

Shorter-term therapies are problem focused, helping you to manage overt issues. They are usually structured and clear goals and techniques are laid out. There may be questionnaires and other forms of measurement to track your progress.

For individuals with more severe dysfunction, complex trauma histories, and histories of hospitalization, therapy is like to be long-term. A study highlighted in Dr. Friedman’s article demonstrated the superiority of psychodynamic treatment for these issues over more short-term symptom-focused approaches.

Long-term does not, however, mean indefinite!

Even with the most difficult of situations, therapy eventually outruns its usefulness. For some, it might just be that therapy has done all it can and perhaps some other lifestyle or wellness program might be of more benefit. For others, it might be the type of therapy needs to change or that the individual therapy relationship has gotten stale. Regardless, just because long-term therapy might be needed doesn’t mean that it should go on forever.

Long-term psychodynamic treatments are still goal-oriented and focused on helping an individual eventually gain the tools and build the support system necessary to navigate their difficulties without the need for therapy. These goals usually include learning to regulate emotions, processing trauma, changing expectations and interpersonal patterns, improving your relationship with yourself, building trust and safety, and fundamentally changing the way you react to life stressors and conflict. These are not goals that can be changed in the short-term, unless, of course, you’re kind of just faking it. But, then, that is also a common goal of psychodynamic treatment – to stop faking it and start being more authentic.

Your therapist should be challenging you towards change and there should be clear progress over time, understanding that the “one step forward two steps back” is also part of the process. Stagnation may arise, but your therapist should also be aware of this and be able to change their approach to move past this stuckness, not acquiesce because it’s easier and more immediately pleasant.

What Therapy is NOT

Although things like mindfulness, relaxation skills, career coaching, cheerleading, nutrition awareness, exercise planning, and managing fears of presentations are all aspects that might be incorporated into therapy, none are in and of themselves, therapy. These are all things that you can get outside of therapy! And, likely, for much less cost with far more expertise.

Therapy is also not a place to chitchat about general life experiences just to vent or have someone listen and validate you. This should be what friends are for. If you don’t have friends for this, therapy should be focused on helping you understand why that might be and changing that. If your therapy feels more like a friendship, at best it might be considered supportive counseling. It’s still not therapy.

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with paying someone to listen to you vent or to confide in without worrying about having to reciprocate or have issues with confidentiality. There has been some kind of figure like this in various tribes and communities since the beginning of humans. This is not, however, therapy.

Nor should it be paid for by insurance, at least not without some limits. For sure, there are plans and company benefits that reimburse for wellness activities, like the gym, acupuncture, and massage. Supportive counseling would fit into this category. And, like those other endeavors, limits on funds paid out and/or sessions makes sense.

Part of the reason that folks who are in distress and experiencing intense dysfunction in their life can’t afford therapy is because space is taken up and rates are lowered due to the saturation of this type of counseling being misconstrued as therapy. This misconception also can lead to a lot of confusion and surprise when someone does encounter a skilled therapist who challenges them. If you find yourself in this boat, I encourage you to stick around for awhile as your surprise might turn pleasant.

When Should Therapy End?

There are some very clear reasons that you should consider ending therapy, separate from a planned ending. Obviously, if your insurance changes, you lose a job, and/or for whatever reason can no longer afford it, that’s ok. There are some low/no-cost options out there. Further, your therapist might be able to work with you on the fee temporarily. If, however, those still aren’t options, then you don’t owe anybody anything. You can always return in the future.

More importantly, therapy should immediately end if you feel that your therapist is crossing boundaries, whether it be physically, by making sexual innuendos or remarks, or by revealing private and personal information about themselves that is not in the very clear service of your growth. If your therapist talks about themselves constantly, or you feel like you have to take care of them, leave.

All therapists will make mistakes, say something inadvertently hurtful, or get distracted from time-to-time. Additionally, the therapy space is one in which long harbored fears, patterns, and feelings will arise no matter how the therapist acts; this actually is the focus of many psychodynamic therapies as it allows us to work through painful experiences in the here-and-now instead of just talking about it. Voicing your concerns in this regard can actually lead towards a lot of movement and progress in the therapy process.

However, if you voice your frustrations or feelings and your therapist gets defensive, gaslights you, becomes punitive and/or withholding, or reacts in any way other than apologetically and with curiosity, it might be a sign that your therapist is ineffective, at best or harmful, at worst. For trauma survivors especially, you need to be working with someone who can work through intense feelings and anger without retribution. If you’re made to feel shame or are shutdown, you might need a new therapist.

If you are seeing a counselor for supportive counseling and it feels more like a paid friendship, clearly this is something that could last forever. That is certainly your prerogative and there’s nothing wrong with that. But, to reiterate, this is not therapy.

The goal of therapy should always be ending therapy, regardless of how long it may take to get there. I frequently find that my clients are quite surprised when I tell them this. They feel awkward or guilty having harbored the instinct that it might be coming time to end; there’s a kind of loyalty or feeling of obligation that makes them believe that somehow they should keep coming to therapy because, well, that’s what people do, right? Wrong. It would be unethical for me to allow those anxious feelings and thoughts to be ignored.

“Therapy comes in many varieties, but they all share a common goal: to eventually end treatment because you feel and function well enough to thrive on your own. ” – Dr. Friedman

Continuing therapy when there is no progress and/or after your goals have been met eventually becomes counter-therapeutic or even outright harmful. Regardless of the type of therapy, there should be clear goals and you should feel like it’s a challenge. If you’re just chit-chatting every session (and that isn’t why you’re there) and you aren’t actually working on anything, or you’ve been stuck for a long time without any movement or change, then that might be a sign that either therapy has come to an end or that you need to seek out a more skilled therapist.

Just because therapy ends, that doesn’t mean that you don’t have problems. Everyone has problems! Forever. Rather, it’s time to stop seeing a therapist when you have learned the tools and built the necessary support system in your life to navigate those problems without professional help.

It also doesn’t mean that there won’t be setbacks or times where a professional can be necessary. That’s when you make an appointment. I’ve had many clients “graduate” therapy. At least 10-15% of them come back at some point for a one-off session or even a handful of sessions to work through something or to get back on track. This is totally normal. That doesn’t mean, however, that they shouldn’t have left therapy in the first place.

At the end of the day, if you find yourself stuck and in a therapy relationship that has long since had any sign of progress, it might just be time to take a break. In fact, it is likely just what the doctor ordered.